O summon out of memory Into understanding

So that all may fear it

From the blood and fever

Of our passionate and forever Unregenerate spirit

Such spectacles

As men remember

Of the beautiful, musical

Of flesh, long, limber:

And deduce: how

In the consummate brow

Such cruelties dwell

As into eternity

Flushed the subservient blood, Flattened our silver cities

And covered them with wood.

Frederic Prokosch

from The Assassins, 1936

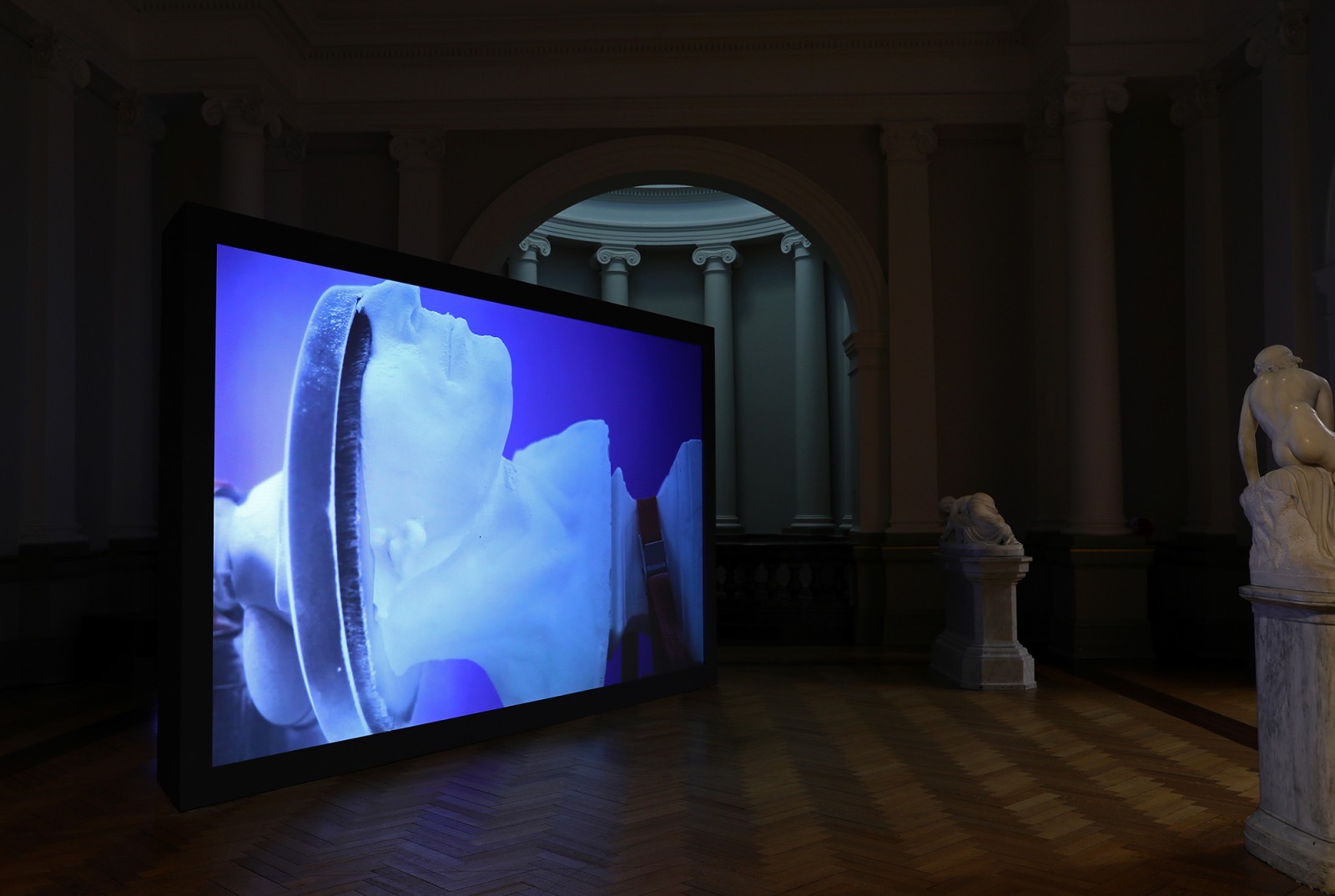

Andrew Hazewinkel’s subject is antiquity, not only its residue materials but also its contemporary spirit. He investigates where antiquity resides now and where it is going. He shows how there is a force in the past. Mixing memory and desire (to borrow T.S. Eliot’s famous phrase from The Waste Land) he shows how this force persists in the present while pushing into the future. And he shows how this force can be accessed artistically as an aesthetic ardour, as an agitation of feelings aroused by culturally charged old fragments that can act, over time, like catalysts for your thoughts and emotions.

To paraphrase the Welsh poet R.S. Thomas, the best artistry “arrives at the intellect by way of the heart”.1 Dionysian as much as Apollonian, equally carnal and mindful, Hazewinkel’s work prompts you to consider the continuous pulse in the past, to channel the animus of antiquity so it might guide your future wishes and actions.

Equally sacred and profane, Hazewinkel plays with the power of enigma and paradox. He imbues stone with bloodwarm tenderness. He brings a soft, breathing waft and welcome into the crisp, cool light that photography tends to demand. He places objects in proximity to one another such that they appear ready to resume some congress that has already happened among them or among their predecessors. And he suggests how we are all not much more than successors to the blooming, broken, bleeding and abraded bodies that are deposited in all the past times that now agitate the spirit of our material contemporary world.

With Hazewinkel’s work I am always reminded of two favourite quotes that I carry in my notebook:

1) Robert Pogue Harrison’s assertion that we must absorb the legacy of the past while enacting our most noble rituals so we can make sure that all those people and actions that have thus far composed history can be kept active in the eternally unfolding now ... ... ... “Whatever the rift that separates their regimes, nature and culture have at least this much in common: both compel the living to serve the interests of the unborn ... [But the special aspect of human memory-work is that] culture perpetuates itself through the power of the dead.” 2

and

2) Michel Serres’ insistence that “Time is paradoxical; it folds or twists; it is as various as the dance of flames in a brazier -- here interrupted, there vertical, mobile, and unexpected. The French language uses the same word for weather and time.” 3

This is what you sense in your heart and then grasp in your intellect, when you encounter Andrew Hazewinkel’s work: the past does not necessarily diminish orderly or die down to a vestige along some perspectival cone. Rather, as Hazewinkel’s work helps you feel, all the dead and gone are actually hard to eliminate. They are in the present, equally pressing and available right now, like a storm looming to animate the atmosphere.

After Hazewinkel’s work rouses your aesthetic faculties, it gets you thinking about how time is energetic and ever-present, thinking about how every past personage and occurrence somehow actually remain in our fears and wishes, still mixing our memories and desires.

These notes composed by Ross Gibson were first published in the exhibition catalogue The National 2019: New Australian Art which accompanied the second edition of exhibition with the same title. The stanzas from the poem The Assasins by Frederick Prokosch were selected for inclusion by Gibson.

1. R.S. Thomas “Don’t Ask Me” in his Collected Later Poems 1988 - 2000, London: Bloodaxe Books 2004, https://www. scribd.com/read/353173913/Collected-Later-Poems-1988-2000#

2. Robert Pogue Harrison, The Dominion of the Dead, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2003, p.ix.

3. Michel Serres with Bruno Latour, Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time (translated by Roxanne Lapidus), Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1995, p.58

DOWNLOAD A PDF HERE