AH

ABSTRACT

In this paper, Cognitive Archaeology’s Material Engagement Theory (MET) is engaged to consider some of the current material interests and aspects of the social dimension of contemporary photographic practice in relation to photographic archives. First the social fabric at the foundation of the John Marshall Photographic Collection and the research methods and working practices of its founder are described. Then, three contemporary photo-mediated artworks (whose inception lies with archival material drawn from the John Marshall Photographic Collection held at The British School at Rome), are discussed through a framework of MET’s three working hypotheses. These are the hypothesis of the extended mind, the hypothesis of enactive signification and the hypothesis of material agency. By drawing together the current material and social interests of contemporary photographic practice with MET (in specific relation to archival photographic material), this paper aims to shed new light on some of the diverse ways in which contemporary photographic practitioners are engaging with photographic archives. Presented here is a preliminary introduction of contemporary photographic practice to the practical applications of MET’s three working hypotheses, so that practitioners in the fields of cultural materials conservation, contemporary photographic practice and archaeological theory may further consider these applications in their own practice-based activity and discourse.

INTRODUCTION

In the spirit of interdisciplinarity, this paper aims to engage readers from the diverse fields of cultural materials conservation, photographic archives, archaeological theory and contemporary photographic practice. It draws upon concepts and at times specific language from each of the contributing fields. In doing so the author aims to open up a blended space in which productive thinking may lead to practical exchange between practitioners working in each of the contributing fields. The paper is composed in two parts. The first consists of the Introduction and a section focussing on the establishment and social development of The John Marshall Photographic Collection (referred to throughout as the Marshall Collection), held at The British School at Rome (BSR) Archive. Examination of this Collection will provide the reader with an example of the photographic archive, highlighting its role as a repository of knowledge and cultural memory. By introducing the material and social history of the Marshall Collection (how it developed and why), this paper reveals the function that archival material can play in contemporary photographic practice. This is explored more closely in Part 2 through the analysis of three photo-mediated artworks. In addition, consideration of this Collection’s biography, nature and significance will help to shed light on the practical applications of Material Engagement Theory in the artworks discussed.

The second part consists of two case studies which are considered with the aid of the three working hypotheses of Material Engagement Theory (MET)1. Case Study 1: From Limbo to Mashup discusses two contemporary photographic artworks (by the author), that were inspired by early 20th century gelatin dry plate negatives from the Marshall Collection. In this discussion MET’s hypothesis of enactive signification and the related concept of material semiosis 2 are outlined and used as a means of artwork analysis. Case Study 1 then considers subject / object relations, focussing on the expressive potentials inherent in the conceptual conflation, or melding, of the material object and its subject. Case Study 2: The Spell of the Fake considers a contemporary photographic sculpture (by the author) whose inception lays with two gelatin silver photographic prints in the Marshall Collection. Case Study 2 introduces MET’s hypothesis of the extended mind 3 as a means of considering the material presence of the contemporary sculpture. It then returns to the hypothesis of enactive signification and the concept of material semiosis which are further explained through the process of artwork analysis. Next MET’s hypothesis of material agency 4 is introduced in relation to the social histories embedded in the photographic practices associated with the trade of antiquities.

This paper aims to provide readers with an introductory understanding of MET for the purposes of practical application. However, it is important to acknowledge that it is not within the scope of this paper to provide a detailed analysis of all aspects of MET’s complex thinking about the relationship between the materiality of things and cognition. Where pertinent, detail relating to its three working hypotheses and further references can be found in the accompanying notes.

While reading this paper it is helpful to keep in mind a distinction between the properties and the qualities of materials. Here the properties of a material can be understood as its physical characteristics - cold, hard, granular, soft, slippery etc. The qualities of a material are the socially constructed ideas which society collectively imbues a material with - the sense of romance associated with diamonds, the rusticity of terracotta, the value of gold, and the celebratory nature of champagne are all good examples. It is also relevant to acknowledge that the study of collection histories plays an important role in author’s creative practice, through which archival historiographies are reinterpreted in the processes involved in an artwork’s conception and development.

THE JOHN MARSHALL PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION

The Marshall Collection is one of several that comprise the holdings of the BSR Archive, a repository of historical material that includes printed photographs, photographic negatives, maps, prints, manuscripts, works on paper, documents and administrative records pertaining to the host institution. The Marshall Collection is modest in scale and is arranged in two materially distinct categories. The glass negatives component of the Collection comprises approximately 800 gelatin dry plate negatives, and the printed photographs component comprises approximately 2500 gelatin silver prints, most of which are referenced in a correlated card index. The principle subject of the Marshall Collection is Greek and Roman sculpture. This reflects Marshall’s foremost area of expertise, for which he was highly esteemed.5

John Marshall (1862-1928) was born near Liverpool, UK on 10th September 1862. At age nineteen he entered New College at Oxford on a scholarship, graduating in 1885 first class in Classics. In the year before his graduation he became friends with and then the intimate partner of Edward Perry Warren (1860-1928), a young Bostonian millionaire and collector of antiquities. Prior to meeting Marshall, Warren had studied Classics at Harvard before also attaining first class in Classics at Oxford (Crauford 2003, p. 100).Marshall and Warren’s lives quickly became entwined. Marshall became Warren’s secretary and for twelve years they lived together at Lewes in East Sussex where Warren established a fraternity of similarly minded male aesthetes devoted to the Greek ideal. During those early years together Warren’s practice of collecting antiquities deepened. Together they often travelled to Rome where a large number of Warren’s acquisitions were made. Rapidly, in London and Rome, the pair developed a reputation for expert scholarship and prudent acquisition. It was during this period that a British Museum spokesman suggested ‘Warren and Marshall controlled the entire Grecian art market’ (Crauford 2003, p. 100). In November 1907 Marshall left Warren and Lewes to marry Warren’s cousin Mary Bliss. Marshall and Bliss then settled permanently in Rome.

During their Lewes years Marshall and Warren became professionally involved with Edward Robinson of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (MFAB). Together they played an important role in developing the museum’s Greek and Roman Collection, which at the time was considered the premier collection of Greek and Roman art in the United States of America. In 1906 Robinson moved from the MFAB to take up the role of Assistant Director at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He was the first trained classicist to be appointed to the museum and in the same year he appointed Marshall exclusive European Agent, a position that Marshall held until his death in 1928 (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2018).

Working from Rome as both a scholar and agent, Marshall developed research methodologies and working practices that met the needs of these dual roles. His collection is characterised by the melding of these practices. Bernard Ashmole (1894-1988), an authority on classical sculpture and Director of the BSR at the time of Marshall’s death, described Marshall in the following extract from the BSR Annual Report for the year 1927-28:

He combined sensitive judgement, enthusiasm and fine humour with an intolerance of undue theorising, and although he was not widely known, wherever he was known his high ability as a judge of ancient art was fully recognised. (British School at Rome 1927-28)

The use of photography as a research tool for art historians, classicists, dealers, agents and others involved in the trade of antiquities was well established before Marshall commenced his role as European Agent to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Marshall’s friend and colleague, the now famous art historian Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), is known to have exclaimed ‘Photographs! Photographs! In our work one can never have enough’ (Berenson 1932, in Acknowledgements). During Marshall’s career photographs were circulated widely across all professional strata associated with the study and trade of antiquities. Photographs were not only valuable research tools they were also useful in restoration processes and could also be applied to the manufacture of forgeries.

In addition to the material subdivision between the glass negatives and the printed photographs of the Marshall Collection, further classification can be made by considering how Marshall met the diverse needs of his scholarly practices and his trading activities. One of these classifications is Marshall’s reference collection, sometimes referred to as the Study Collection. It comprises principally photographs of well-known works of art documented by photographers who (for the most part) remain anonymous. It also includes rephotographed copies of images made by highly specialised, well-known photographers and photographic studios such as Fratelli Alinari (Florence) and Adolphe Giraudon (Paris).

Marshall arranged his printed photographs into various categories. Category A contains photographs of objects that he acquired for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, these are sometimes poor-quality images presumably supplied to Marshall by dealers or others. Some of these poorer-quality photographs can be paired with related ‘after’ images. These ‘after’ images were commissioned by Marshall once their ancient subject had been purchased, cleaned and restored or study copies had been made. Marshall commissioned a large number of these ‘after’ images, many of which were created by the Roman photographer Cesare Faraglia with whom Marshall maintained a long professional association (Crauford 2003, p. 100). The negatives of these commissioned photographs comprise a large part of the glass negatives component of the Marshall Collection.

Categories B and C contain images of sculptures and other objects that Marshall was offered but did not acquire. From these he further classified those objects he thought to be suspicious or forgeries. Category D photographs represent objects that Marshall was not offered. These images were rephotographed from a range of sources and they represent objects considered by Marshall to have the finest or most desirable qualities.

Understanding Marshall’s system for cataloguing printed photographs allows us to think about the glass negatives of the Collection in a unique way. Knowing that Marshall and Faraglia maintained a long, close working relationship (and that many of the glass negatives were created by Faraglia), we are able to consider the glass negatives as a body of photographic work in which Marshall had the potential for creative input. Thus far research on the Collection does not reveal any hard evidence of this and there is no evidence to suggest that Marshall made photographs himself, but it is likely that a close working relationship developed between the two, and that this relationship is likely to have included discussions about the expressive potentials of different lighting styles, framing, camera angles and so on. From a photographic practitioner’s perspective, it would be unusual for such a creative working relationship not to have developed.

Comparing the ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs of Category A, photographic historian Alistair Crauford explains the role that photography played in the promotion of certain values inherent in the commercial enterprise caught up with the trade of antiquities.

With such “before” and “after” states, the photographer assisted in providing evidence for the values discovered by the dealer or curator, values that could not, by implication, have been seen by ordinary eyes. It is the application of the craft of photography to remake, in a certain image, the virtues, the value system, applied by the connoisseur to an object. This in turn provides the audience with more tangible, visual “evidence”, a more accurate, appropriate aura. Transformed by the unique abilities of the seer, the buyer — in this case John Marshall — the object, once cleaned and restored and appropriately photographed, is able to reveal once more the sculpture’s true inner values. (Crauford 2003, p. 106)

CASE STUDIES: BACKGROUND

The following case studies address the material and conceptual concerns of three contemporary artworks situated within the expanded field of photographic practice. In this context the expanded field of photographic practice can be understood as the field of creative activity that is principally informed by any one (or coalition of) the following: the history of photography, photographic theory, modes and practices of photographic image production (and reproduction), photographically-informed objects and photographically-generated images made with or without cameras.

The case studies aim to demonstrate how the current material interests and aspects of the social dimension of contemporary photographic practice can be explored by engaging with archival material and by considering these creative processes within the conceptual framework of MET’s three working hypotheses - that of the extended mind, enactive signification and material agency (see notes 1, 2, 3 & 4). It is also intended that the analysis of the contemporary artworks discussed in the case studies reveals a multilayered material and conceptual correlation between the immortalising impulse embedded in the early history of photography, the preservation and conservation principles central to archives, and the subject matter of much of the Marshall Collection (which has funerary and memorial association).

Simply put, MET presents us with fresh ways of considering the relationships between the materiality of things and how we think. It emerged relatively recently from the field of archaeological theory known as Cognitive Archaeology. MET was developed principally by Lambros Malafouris (2004, pp. 52-62) upon solid foundations laid by Colin Renfrew (2004, pp. 22-32) and others. MET distils complex thinking about the how the materiality of things helps to shape the human mind. A detailed analysis of MET is beyond the scope of this paper, however for readers less familiar with archaeological theory it is helpful to keep in mind the aforementioned distinction between the properties and qualities of a material. This distinction lays fertile ground for questioning what actually happens when they come together. It is proposed that at the convergence of a material’s properties and qualities a very special blending occurs - the physical and the conceptual coalesce, the individual and the collective merge, the immediate present and the remote past commingle.

This concept becomes richer when we consider (as social anthropologist Timothy Ingold does) that the properties of materials are not static physical attributes, but rather dynamic, processual and relational (Ingold 2007, p. 1). For Ingold, the properties of a material describe its present condition on its journey through the world. He considers that the properties and qualities of a material are not entirely separable, rather that they are co-actively relational. Case Study 1 examines a closely related form of this effective reciprocity, which occurs between the materiality of a glass negative and the materiality of its subject (here, a badly damaged figurative sculpture). First however, it is useful to highlight an important event embedded in the early history of photography, wherein the sense of sight and the sense of touch converged.

It is a little known fact that the very first photographic exhibition included not only visual proof of the fixing of an image created within a camera obscura, but that a tactile experience made a vital contribution to the visual experience. On 25th January 1839 (seventeen days after F. Arago announced to the French Academy of Sciences that L.J.M Daguerre had discovered a process to fix the image created in a camera obscura), H.W. Fox-Talbot presented tangible visual proof of the successes of his own proto-photographic experiments. That evening, as the regular Friday lecture at London’s Royal Institution ended, all were invited into the library to view the world’s first photographic exhibition (Hazewinkel 2015, pp. 17-22). During this intimate public display Fox-Talbot’s photogenic drawings and contact prints were passed from hand to hand. In those perceptually world-changing moments, the senses of touch and sight converged in helping the viewer to understand (and experience) a fixed moment of time already passed. This sets us thinking about the expressive implications and the conceptual potentials that arise where the materiality of an image-bearing substance and the image it bears converge; or, in the language of the archive, at the convergence of an information carrier and the information it carries.

CASE STUDY 1 : FROM LIMBO TO MASHUP

Case study 1 moves between the suspended temporal limbo of the dry plate negatives of the Marshall Collection and the multi-periodic mashup of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; via the early history of photography. More specifically, through the analysis of two contemporary photographic artworks (by the author) that were inspired by early 20th century gelatin dry plate negatives from the Marshall Collection. This discussion considers the relationship between subject and object through the MET hypothesis of enactive signification and the related concept material semiosis.

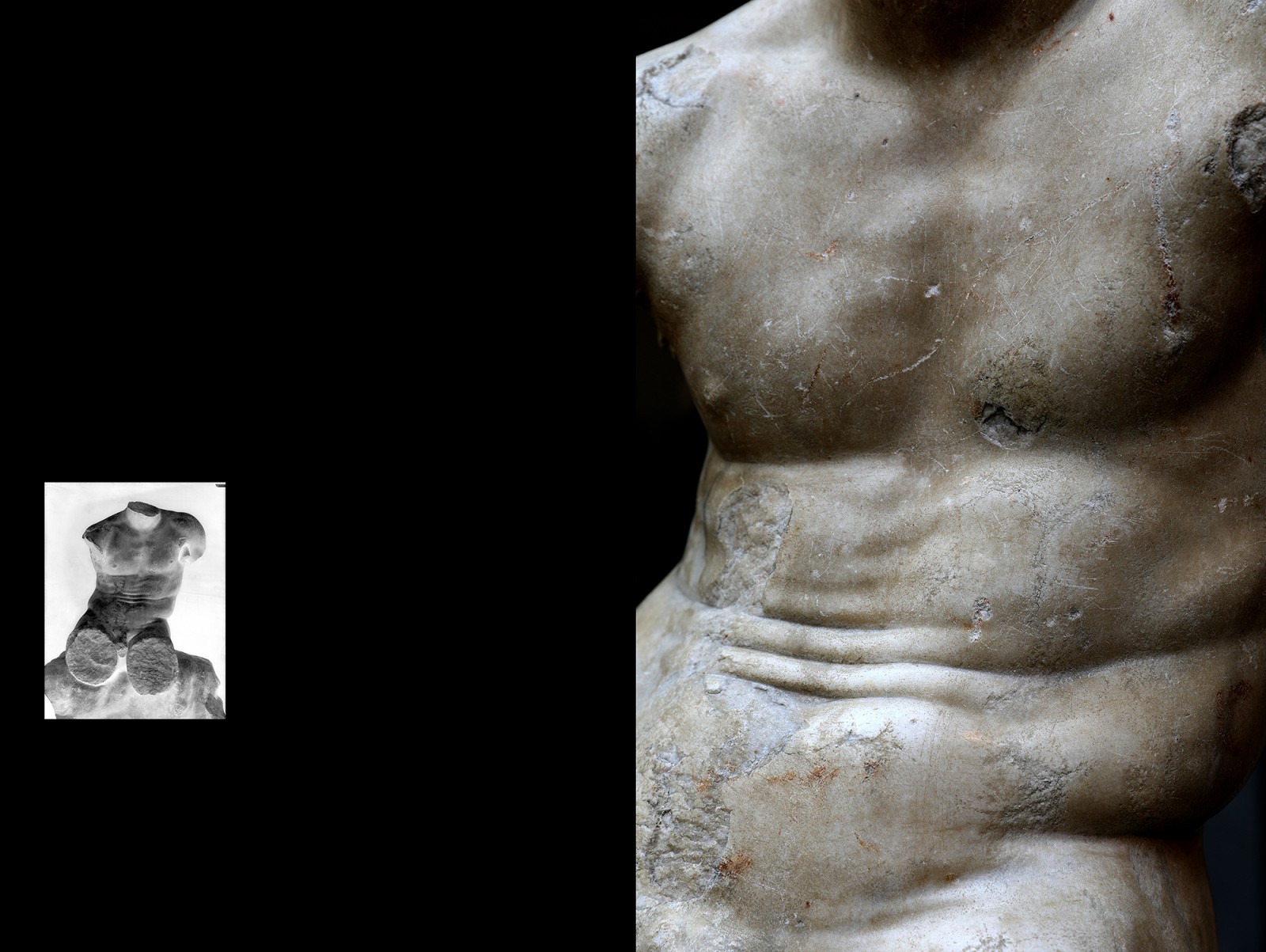

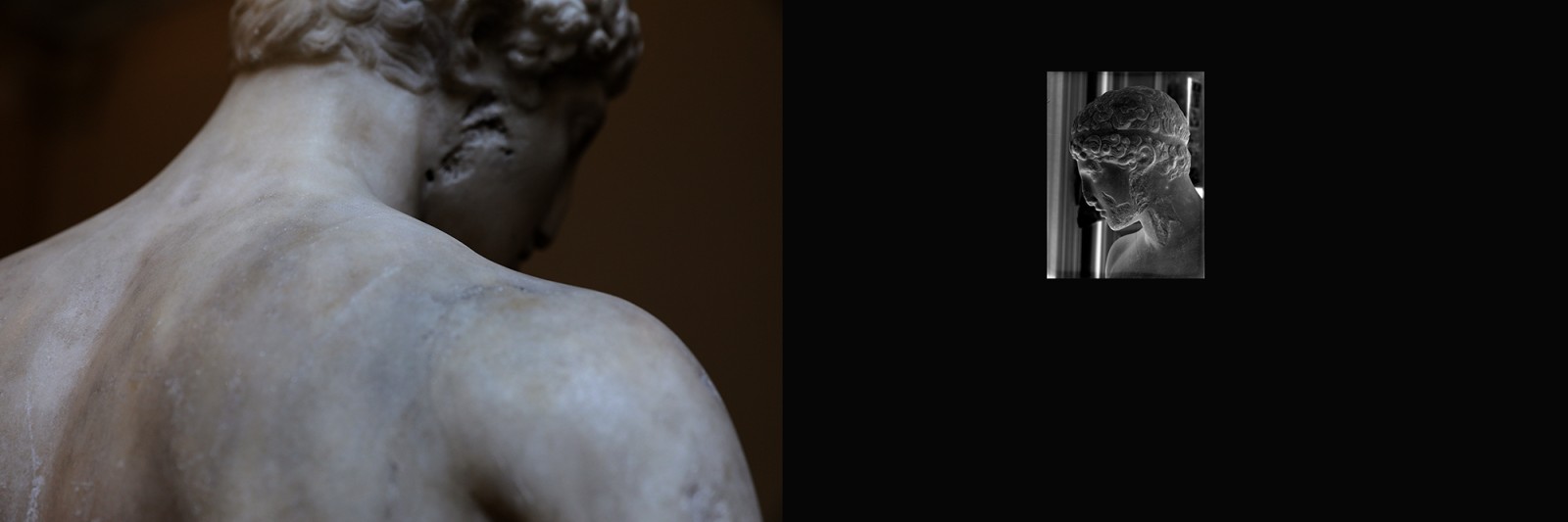

It is clear in the following case studies that direct links exist between the contemporary artwork and ancient artwork represented in the associated archival material. The sculptural subjects of the archival material are today on display in Gallery 162 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which is where the author photographed them in 2017. However, the author’s first introduction to these broken bodies was as images in negative on small sheets of glass in the BSR Archive in 2006.

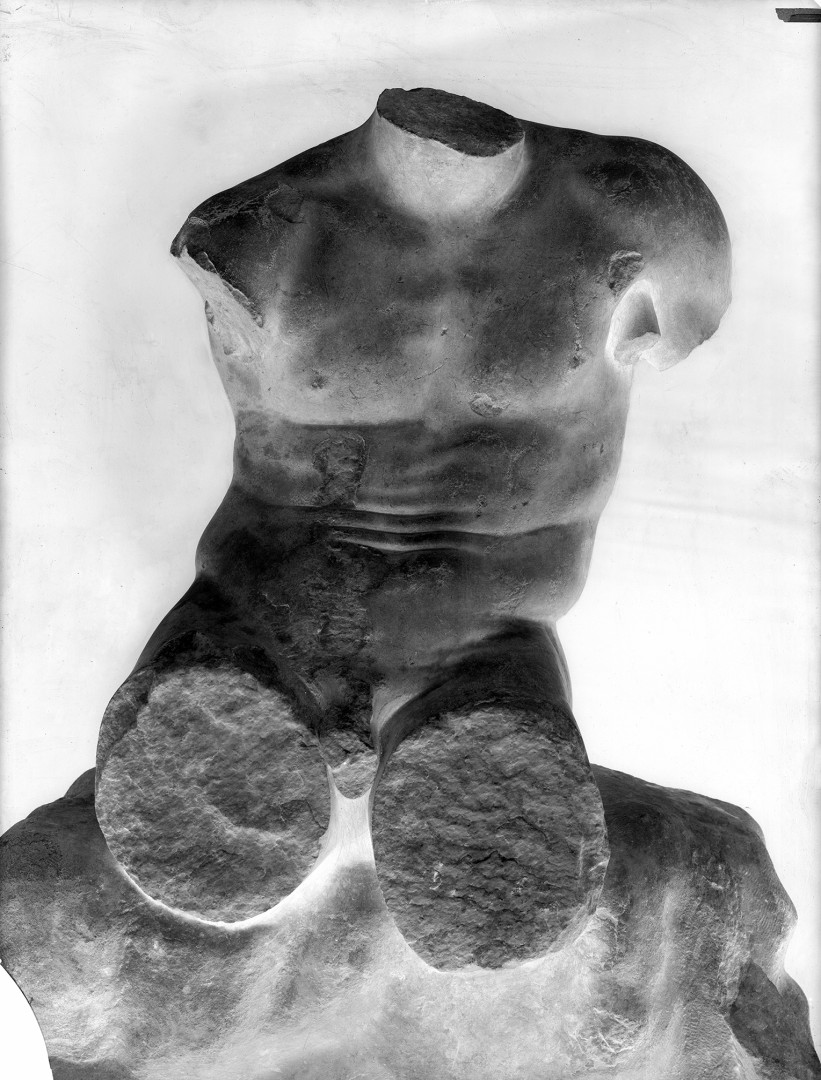

Figure 2a is a digitised reproduction of JM 758 which represents the archival source material for the contemporary artwork (in progress) represented by Figure 2b. JM758 is one of a group of nine negatives representing a 1st or 2nd century CE marble statue of Hercules seated on a rock. Measuring 39.5 x 29.7 cm it is one of the largest gelatin dry plate negatives in the Marshall Collection.

nitial examination of Figure 2a reveals a badly damaged statue that has been documented with its immediate surroundings masked out. The visual strategy of masking out the immediate surroundings focuses our attention on the surviving torso of the young Hercules whose legs,arms and head are all missing. The curvature of the torso and the presence of what appears to be the remains of a physical support tucked into the left armpit suggests a body at rest after strenuous activity. The affronting nature of the breaks where the limbs once joined this spectacular torso appear to have been intentionally created (we cannot be certain), however they bring to mind a sense of violence and an associated vulnerability.

Looking more closely we can identify an easily overlooked break in the plate’s lower left corner, the nature of which reminds us that Figure 2a is captured on glass. The break in this glass artefact manifests an equivalence between the object (a damaged glass negative) and its subject (a damaged torso). Through this materially-triggered conceptual correlation, new meaning emerges at the convergence of the material, conceptual, philosophical and mythological dimensions. By mirroring the breaks in the sculpted body represented on the glass plate the break in the glass plate enables us to sense (in a physical way) a vulnerability in the representation of an identity famed for invulnerability 6. This correlation between the materiality of the object and its subject can be considered an example of enactive signification.

The hypothesis of enactive signification concerns the semiotic dimension of materials. In accordance with this hypothesis the material sign is understood as a part material, part mental entity, which brings meaning to light through action. Here ‘action’ should be understood as the various ways in which humans engage with a material, and thereby play a vital role in creating the meaning of a material. We enact a material’s meaning in the moment of our physical and mental engagement with it. To put it another way, the hypothesis of enactive signification conceives of the material sign as a synthesised form of meaning that emerges through the materially-triggered (conceptual) blending of physical and mental forms of perception.7

Here it is important to understand that the semiotic dimension of materials function through a logic that differs from the representational logic that linguistic semiotics rely upon. A simple way to understand this is that the semiotic dimension of language is dependent upon the preestablished, symbolic, representational meaning of words; whereas in the semiotic dimension of materials meaning emerges in the blended space that is created when one’s physical (bodily) and non-physical (mental) experiences of a material merge. It is in this way that we enact and bring forth a material’s meaning. Malafouris expresses this succinctly when he states ‘Material Signs have no meaning in themselves they merely afford the possibility of meaning … material signs do not represent; they enact. They don’t stand for reality; they bring forth reality’ (Malafouris 2013, pp. 117-18).

Figure 2a is integrated into Figure 2b in which the archival image (JM758) is brought together with an image (of the same subject) captured by the author at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the contemporary image of Figure 2b the torso has been reframed in an attempt to reduce the apparent sense of brutality that is triggered by the breaks in the ancient sculpture. Reframing the image in this way aims to lessen the accumulative emotional impacts that we experience through over-exposure to images of violence. This is not to suggest that the sense of violence inherent in the archival image has been erased in the author’s contemporary rendition of the same subject, but rather that its apprehension is now available only through a sense of intimacy with the subject; by getting up close to the chips, marks, scrapes and scars evident on the torso. In other words, by reframing the broken sculpture in this way the perceptually blinding sense of brutality evident in the archival image is lessened and thereby makes the sense of vulnerability embodied in the broken figure more accessible.

This way of thinking about making images that are inflected with violence has been influenced by Slavoj Žižek’s proposed benefits of looking at the problem of violence obliquely. He states his premise for this in his book Violence: Six Sideways Reflections.

My underlying premise is that there is something inherently mystifying in a direct confrontation with it: the overpowering horror of violent acts and empathy with the victims inexorably function as a lure which prevents us from thinking. A dispassionate conceptual development of the typology of violence must by definition ignore its traumatic impact. (Žižek 2008, p. 4)

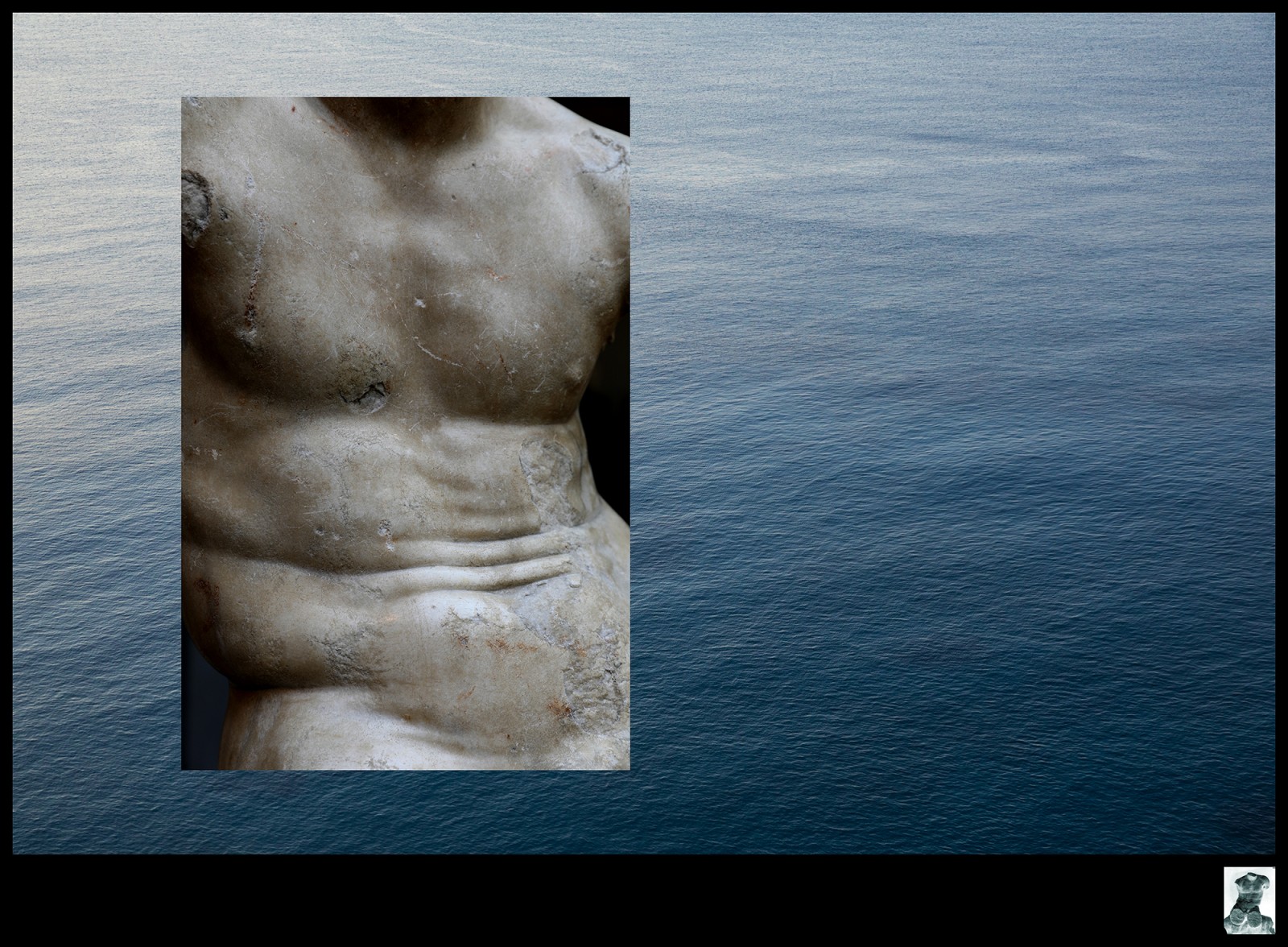

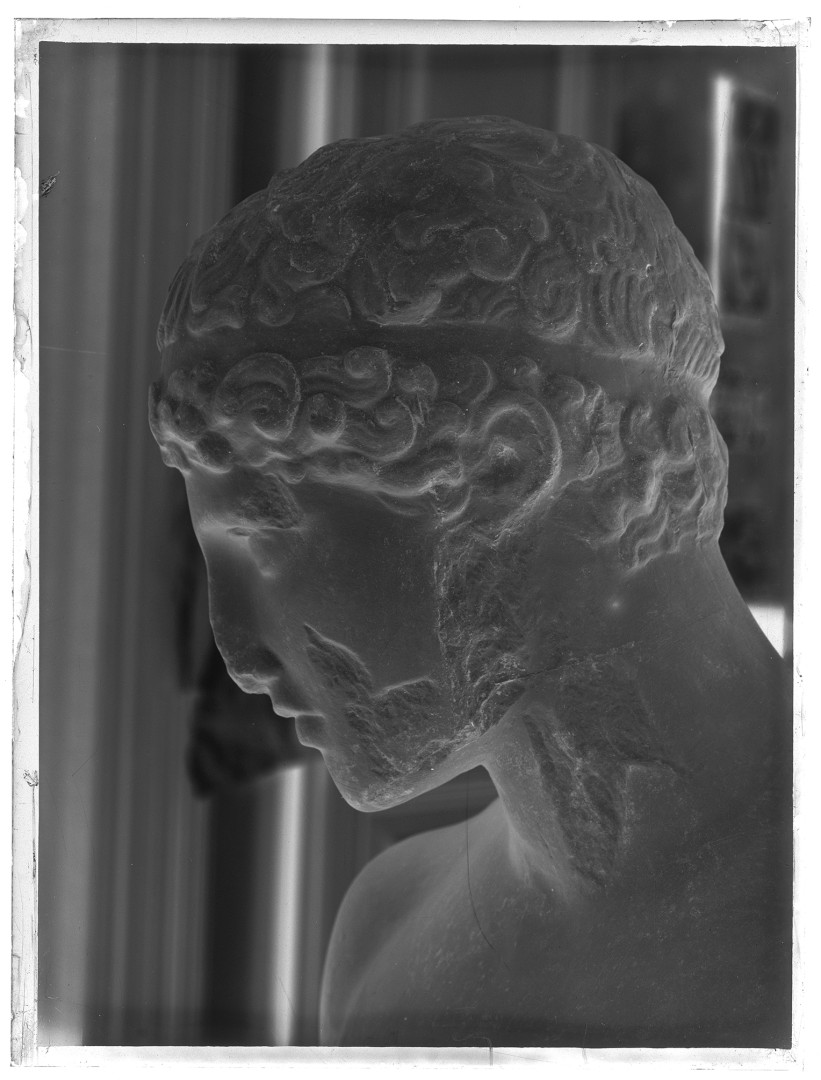

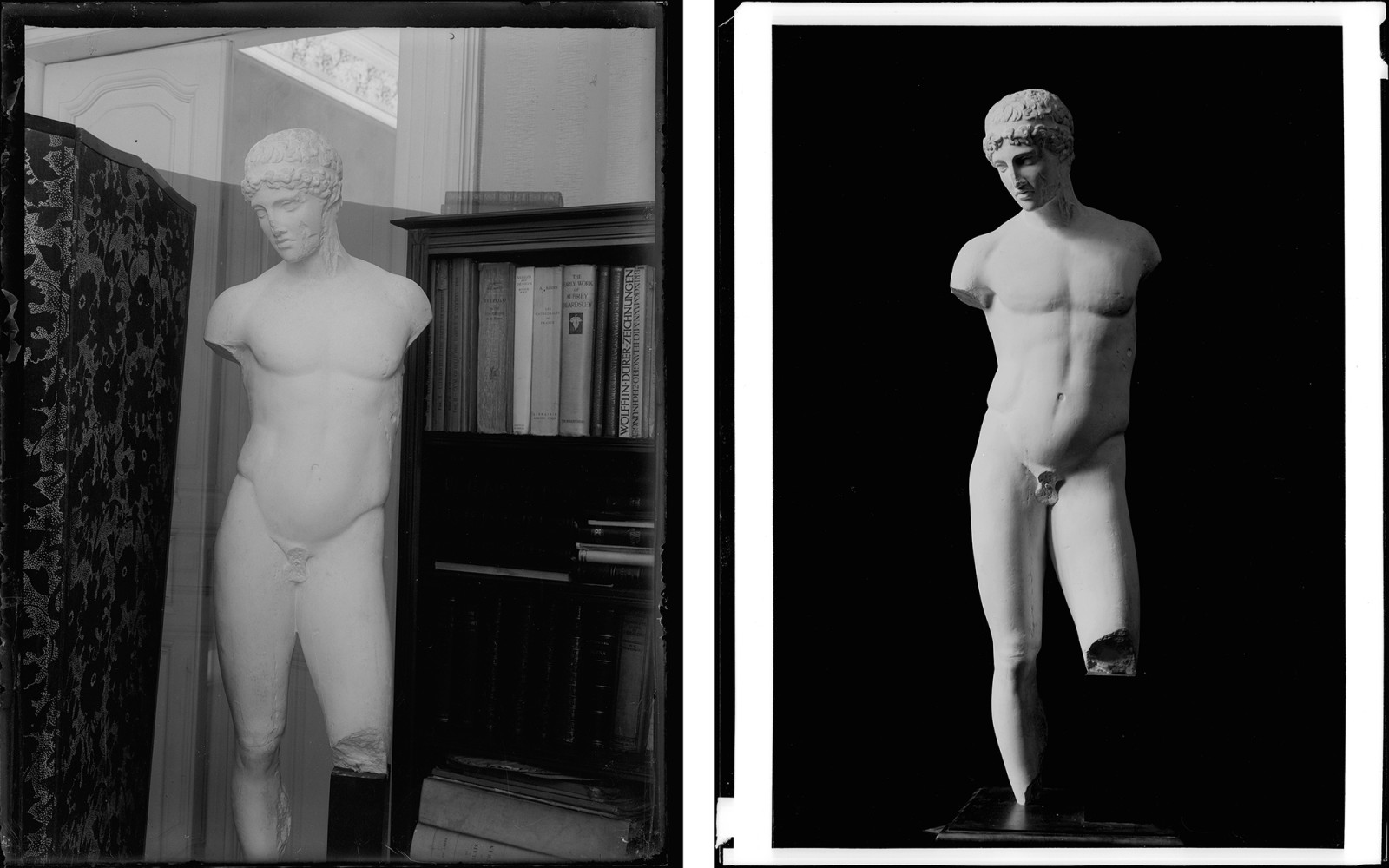

Figure 3a is a digitised reproduction of JM777, a gelatin dry plate negative measuring 10.7 x 8.1cm which is the archival source material for the artwork (in progress) represented by Figure 3b. In it we can see in profile the head, neck and shoulder of a plaster replica of a Greek statue of a youth, carved of Pentellic marble during the 1st century CE. JM777 represents one of eleven negatives documenting various views of the same subject.

Figures 4a and 4b represent ‘before’ and ‘after’ images. In Figure 4a (JM779) the object is photographed in a domestic setting, in Figure 4b (JM 482) it is photographed under studio conditions. These two related images illustrate Marshall’s working practice of rephotographing certain objects to support poorer-quality images. One of the most interesting aspects of the smaller negatives (JM 774–780) is that they appear to be photographed in Marshall’s personal setting. In these images no attempt has been made to obscure the intimate surroundings; we can clearly see not only the plaster copy of the ancient torso, but we are also given a view into Marshall’s private world. We can see his books, his choice of furnishings and other objects. We see Marshall all around the photograph’s intended subject, in other words these images have two subjects.

Comparing Figures 4a and 4b sets us thinking about the creative potentials inherent to the archive cataloguing glitches that can occur when working with personal collections. This is exemplified by the way in which the author first encountered this group of seven negatives (JM 774-780). Outside the main body of the glass negatives of the Marshall Collection, at the back of a cupboard in the BSR Archive office, the author found an old cardboard packaging box (ca. 1926) commercially labelled ‘Gelatin Silver Bromide Glass Plates’. Their subject was immediately recognisable from the larger negatives JM 482-485 (Box JMC5), which the author had studied during a survey of the entire glass negatives collection between 2007 and 2014. Although the four larger negatives may be considered by some to be better quality images (or perhaps more technically proficient), they hold less information and are, personally speaking, of less interest than those created in Marshall’s personal setting. In the smaller negatives we encounter not only the subject of Marshall’s gaze but also Marshall himself.

Crauford focuses solely on the subject of the ‘after’ image when he states ‘the photographer assisted in providing evidence for the values discovered by the dealer or curator, values that could not, by implication, have been seen by ordinary eyes’ (Crauford 2003, p. 106). It is unknown whether Crauford saw the seven smaller ‘before’ negatives. It appears however, that his research tended to focus on the printed photographs of the Marshall Collection. While it is apparent that some of the unboxed seven negatives were printed 8 and that Crauford considered those images, it remains unclear whether Crauford saw this set of negatives. If Crauford did see these negatives, it would seem as though they were of little interest - or, that information that could be considered by ‘ordinary eyes’ (information concerning Marshall himself) was deemed less important than the information revealed for the connoisseur’s gaze, information concerning the ancient sculpture.

This brings us to the issue of intentionality and the related issue of affordance, both of which are important considerations in understanding the hypothesis of material agency. In the following paragraphs the author has endeavoured to provide a working introduction to these complex issues while acknowledging that a detailed explanation of their complexity is beyond the scope of this paper.

Malafouris (2013, p. 136) defines intentionality as a philosophical problem that (in contemporary philosophy of mind) is generally understood as a fundamental human property in which mental states are ‘directed at, or about, or of objects and states of affairs in the world.’ To put it in simpler terms, intentionality is conventionally understood as a ‘strictly internal phenomenon of human consciousness with no counterpart in the realm of things’ (Malafouris 2013, p. 137). Malafouris, however, suggests that the definitions above do not apply in all instances; therefore he turns to philosopher John Searle’s distinction between prior intention (which refers to premeditated actions) and intention in action (which refers to non-deliberate everyday activity in which no intentional state was formed prior to the action itself) (Malafouris 2013, pp. 137-138). In doing so, he draws our attention to the importance of intention in action in MET’s conception of material agency, which proposes that ‘agency should not be perceived as a fixed property of humans but as the emergent product of our engagement with the world.’ (Malafouris 2013, p. 148)

The concept of affordance, coined by the psychologist J.J. Gibson (1979), denotes the ‘possible action of a thing.’ Malafouris highlights the way that the term underlines the interaction between the physical properties of things and the experiential properties of an observer. In his words,

the affordances of an artifact are objective (as they exist independent of any valuation or interpretation - being or not being perceived), but at the same time they are subjective (as they necessitate a point of reference). An affordance is always an affordance in relation to the action capabilities of something. It is simultaneously objective and relational. (Malafouris 2013, p. 252)

Comparing Figures 3a and 3b through the hypothesis of material agency presents another way to consider the social dimension of this archival material, more specifically, by considering the intentionality and affordances of the establishment of the Collection. Briefly described, the hypothesis of material agency conceives of agency as the ability of an object to effect change upon the world. It proposes that material agency is not pre-established and does not lie with objects themselves, rather that it manifests during processes of human engagement with an object. According to the hypothesis of material agency, intentionality and affordance are not properties of objects and people respectively, rather they are the constitutively intertwined properties of human engagement with objects. Another way of expressing that is that material agency, intentionality, and affordance do not exist prior to our engagement with objects, but rather they emerge from our engagement with the material world. 9 Considered in this way, the agency of the photographs created by Marshall with Faraglia (and unknown photographers) manifests during peoples’ engagement with them. The intentionality of Marshall to represent the ancient sculptures in a certain light, in accordance with certain social values, is inextricably caught up with the affordances offered by the ancient sculptures shown in this light. Through the contextual setting of Figure 3a Marshall can be considered present in a representationally direct (yet unintentional) manner; while through the de-contextualised setting and lighting style represented in Figure 3b Marshall can be considered present in a representationally indirect (yet intentional) manner.

The author’s approach to working with these photographic artefacts and their subjects is more complex than a chronologically linear, before and after method. The images created by the author differ (not only visually) from ‘after’ images as discussed by Crauford (2003, p. 106). In making images of the same subjects, it is the author’s intention that they bring to the fore a value system not driven by the commercial apparatus often associated with connoisseurship, but rather in the emotional experiences of being human. Marshall and Faraglia’s ‘after’ images were designed to decontextualise their subjects. However the images created by the author are intended to recontextualise the original subject by drawing it into a new, highly personal, human context. In each of the contemporary works, there is a resonant sense of intimacy, a sense of softness that belies our understanding of the material properties of the stone object represented. Although we know that we are engaging with (images of) bodies of stone, these representations aim to inspire a sense of what is here referred to as ‘withness’ 10. These sensations and feelings arise from human emotions and desires, and it is through these sensations and feelings that we are haunted by those who lived in Antiquity, the very person from whom the original sculptor created the body before us.

CASE STUDY 2: THE SPELL OF THE FAKE

In this case study we move between the Iron Age kingdom of Lydia (approx. 1200 - 600 BCE), the suspended temporal limbo of the photographic archive, and the expanded field of contemporary photographic practice. Two gelatin silver photographs from the Marshall Collection are used to introduce the hypothesis of the extended mind, before returning to the hypothesis of enactive signification (and the concept of material semiosis) as a means of considering the materiality of the contemporary sculpture. The hypothesis of material agency is then used as a framework for considering the dynamic interplay between the socially informed agency associated with the archival photographs and the sculpture created with them.

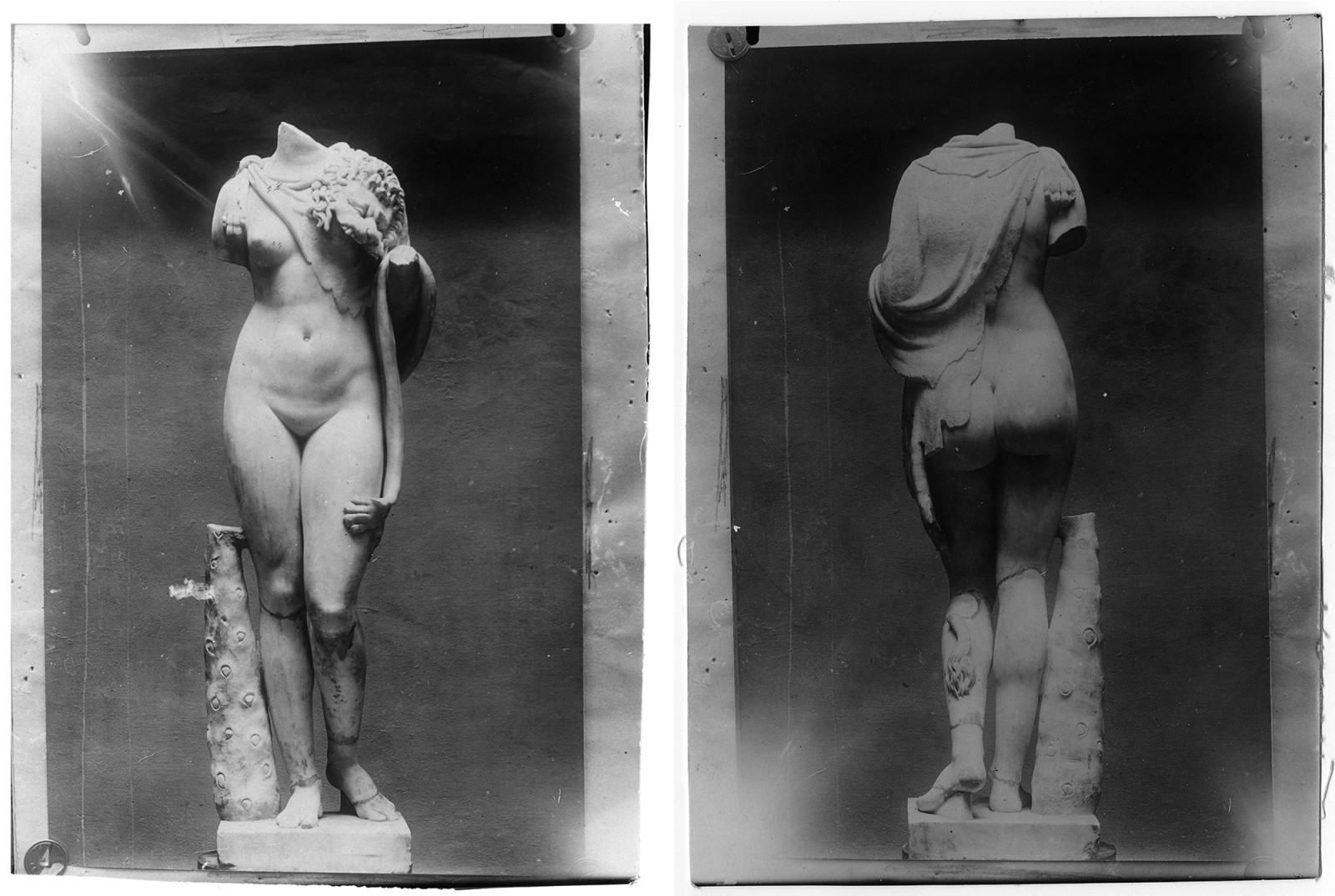

Figure 5 represents two gelatin silver photographs from the Marshall Collection box JM19B labelled Suspicious-Forgeries. These images represent the front and back views of a partially naked female figure whose arms and head are missing. The figure’s identity can be deduced by the fact that she is represented with the classical attributes of Hercules. At her right stands his olivewood club, about her shoulders drapes his lion-skin cape. The subject of these images is a marble representation of Omphale, a powerful Lydian queen. Very little is known of this important personage from Antiquity as she is little represented in Western mythology. The scope and aims of this paper preclude a detailed investigation into the mysterious Omphale, or a scholarly questioning into why she is so little represented in Western mythology, however it is relevant to know a little of her story.

In Greek mythology, Omphale, the daughter of the Lydian king Iardanus, was married to Tmolos the oak-clad mountain-king of Lydia whose reign ended when he was gored to death by a bull. Following the death of her husband Omphale continued to rule Lydia independently. The story most often associated with Omphale is that during her reign Hercules was enslaved to her to atone for killing Iphitus. A condition of the enslavement (apparently stipulated by Omphale) was that the hyper-masculine Hercules remain at her court performing women’s work while wearing only women’s clothing. As part of this gendered role reversal Omphale is said to have worn his lion skin, taken possession of his olivewood club and engaged in men’s activities such as hunting.

Figure 6 (below) represents a contemporary sculpture created with the two archival images above. Suspicious Marble (Omphale) is a large, soft, hanging screen, comprising six leather hides. Screen-printed onto both sides of each skin (at approximately 1:1 human scale) are the archival images. To achieve this, firstly the original gelatin silver photographs were digitised and used to create image-specific dot-screens that were designed to maximise the photographic detail in the screen-printed reproduction. The image representing the front view of the figure is printed onto the tanned leather surface in an opaque white ink; the back view is printed in a pewter-grey, light-reflecting metallic foil onto the light-absorbing suede side of each hide. The skin are sewn together across the top to a depth of approximately 40 cm creating a continuous plane from which each idiosyncratic skin hangs in loose drapes and curling folds.

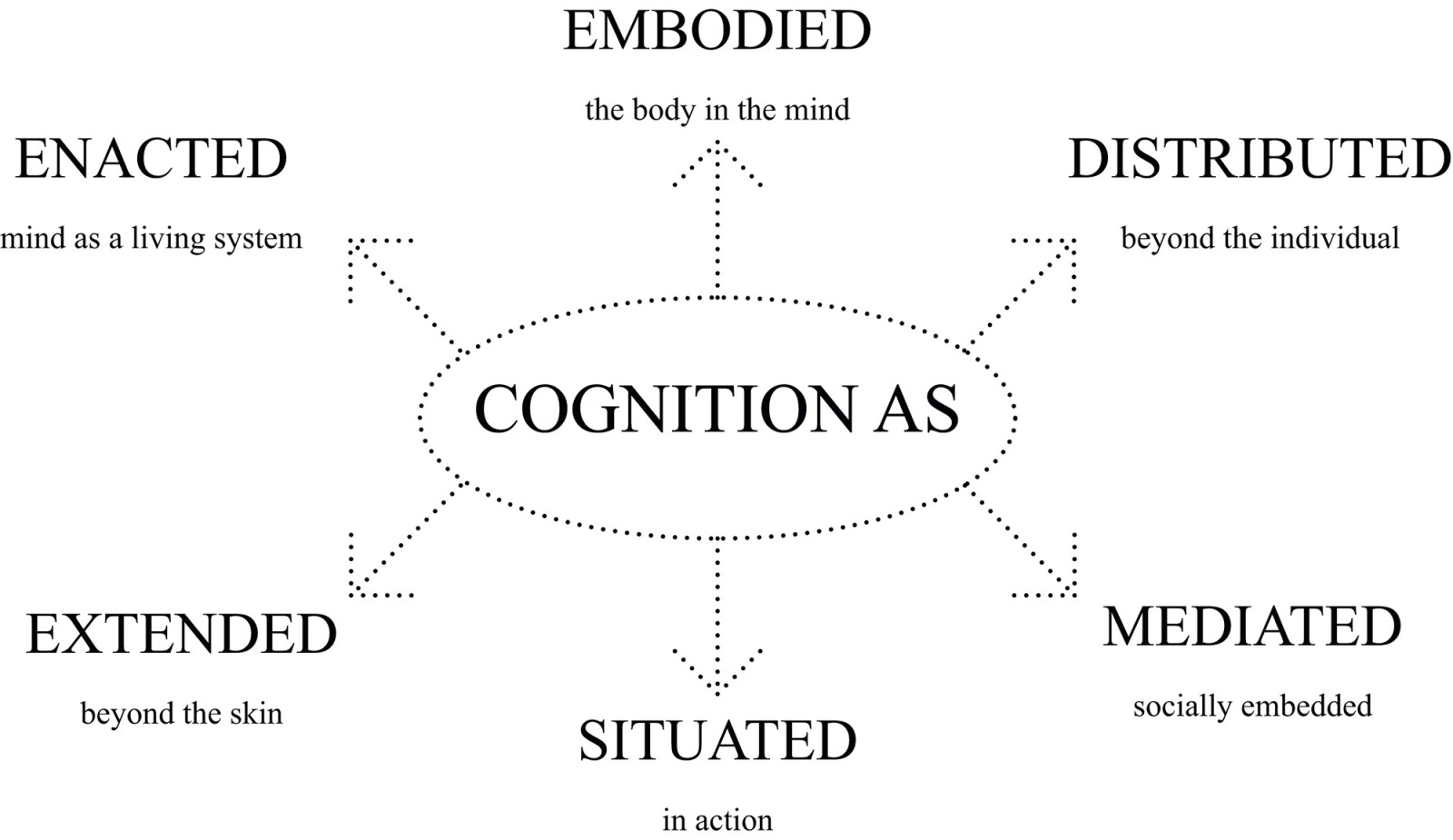

Describing the MET hypothesis of the extended mind, Malafouris states: ‘Thinking is not something that happens “inside” brains, bodies, and things; rather it emerges from contextualised processes that take place “between” brains, bodies and things’ (Malafouris 2013, pp. 77-8). Perhaps a simpler way of expressing this is that according to the hypothesis of the extended mind, thinking is understood as a process that extends beyond the limits of the brain and body and out into the physical world. Figure 7 illustrates Malafouris’s framing of an expanded field of cognition.11 It is included here to help those less familiar with MET to understand the ways that cognition emerges through processes that extend beyond the brain and the body (in accordance with the hypothesis of the extended mind), and how the material sign brings forth meaning though action (in accordance with the hypothesis of enactive signification). To better understand the hypothesis of enactive signification, it is helpful to consider how a sign creates meaning, rather than what a sign means. Another way of saying this is that meaning emerges through a process of conceptual blending of the physical and the mental (Malafouris, 2013 p. 90). This is precisely at issue in the correspondence between the subject of the archival material and the material aspects of Suspicious Marble (Omphale) 2017.

So exactly how does this way of thinking about the archival material inform the creative response? To answer this question we need first to consider the dynamic subject / object relations occurring between the archival source and the contemporary sculpture created with them; because this is where the conceptual blending takes place and from where new meaning emerges. In this example, the archival images are photographic representations of a representation (in stone) of a soft human body, around which is draped the supple skin of another warm-blooded animal. This sets up a layered framework for thinking about the changing role that skin, and representations of it, plays in making the meaning of the contemporary sculpture. By printing the archival photograph (which represents a stone representation of human and animal skin) onto the skin of another animal, a form of enactive signification can be understood to be taking place. This enacted signification is then experienced though extended, enacted, embodied, mediated and situated forms of cognition occurring in the blended space that opens up between the archival photographs and the sculpture created with them. Expressed in the language of the archive, we might say that in the contemporary sculpture a conceptual integration occurs in the exchange between the information carried by the original photographs and the information carrier, in this instance the physical materiality of the contemporary sculpture.

How then might we consider the hypothesis of material agency to further our understanding of the new sculpture? As briefly summarised above, the hypothesis of material agency proposes that agency does not lie with objects themselves. Rather that it emerges through processes of human engagement with objects, and that through these engagements objects play a part in effecting change upon the world. Remembering the issues of intentionality and affordance’s dependence upon intention in action, and considering the concept of material agency in relation to the archival photographs and the sculpture made with them, we are able to identify a multi-layered history of material engagement through which the emergent agency associated with (and through) the original sculpture can be perceived as dynamic and relational.

The following list of engagements presents an historically informed strata of material agency that, through multiple engagements, continues to change. Each material engagement leaves a kind of residual affordance that, over time, can accumulate and colour future engagements. In this instance the first relevant example is Marshall and the unknown photographer’s engagement with their stone subject. This is followed by the engagements (we can only imagine) between the potential buyers of the image subject, which is represented in light of the values that Marshall and his photographer have invested in it. Following these imagined engagements are the author’s archive-based and studio-based engagements with Marshall’s photographs. Lastly and most importantly we should consider the engagement of a person physically experiencing the new sculpture. The intentionality of Marshall and the photographer (in choosing to represent the sculpture in a particular light) is inextricably entwined with the affordances of that sculpture represented in that manner. In other words the intentionality of Marshall and the photographer’s engagement with the sculpture persist residually in the affordances of future engagements with their images of that sculpture.

Herein lies the potential for exploring the social dimension of contemporary photographic practice by engaging with archival material. The contemporary practitioner can work with not only the archival images, but also with or against the intentionality and affordances associated with them. In this instance it is not only the images (generated by Marshall and the unknown photographer) that the author has worked with (in creating the new sculpture), but also traces of their intentionality. In this way the hypothesis of material agency may be considered at work in the process of creating and interacting with the contemporary sculpture. There is another dimension to the expanded field of cognition at work in Suspicious Marble (Omphale). Further meaning emerges through the viewer’s remembered sensations, which arise from past interactions between their own skin and the physical world. The scale of the screen-printed figure is a factor here, in as much as this psychic, sensorial, embodied apprehension is enabled through the change in scale — from the small originals to a scale that mirrors our own bodies.

Lastly, Suspicious Marble (Omphale) comprises six photographic representations of a subject that was originally intended to be experienced ‘in the round’. This very specific form of artwork engagement is more commonly associated with object-based sculpture than with photographs, however by presenting Suspicious Marble (Omphale) centrally within a space the viewer is encouraged to move freely around it. In this way the intentionality inherent in the original subject of the archival photographs is enacted in the presentation of Suspicious Marble (Omphale). An important variation to this mode of presentation is at work here. The historical tradition of ‘in the round’ sculpture has at its foundation the experience of a shared support plane between a viewer and a sculpture- the floor; however Suspicious Marble (Omphale) is suspended from the ceiling. As a result all six bodies seem to ‘hover in the round’. Somewhat paradoxically the stone figure now appears to be weightless. In this way Suspicious Marble (Omphale) aims to give rise, in the viewer, an embodied sense of weightlessness; if this is successful then perhaps the viewer is left hovering conceptually and perceptually in a newly created blended space in which the physical and the mental converge somewhere between the archival source material and the artwork created with it.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this paper was to present preliminary introductions to MET via the analysis of three archivally inspired contemporary photo-mediated artworks. In doing so it aimed to inspire fresh thinking about the ways in which artists might engage with archival material and hopefully lead to future productive collaborations. By introducing practitioners of cultural materials conservation and contemporary photographic practice to MET’s three working hypotheses it hopes to shed light on how MET might be practically applied in their own practice-based activity and discourse. A guiding principle of introduction rather than detailed explanation has therefore been applied throughout. By introducing ideas, concepts and language from the field of archaeological theory, the reader is introduced to new approaches in thinking about archival material and how contemporary photographic practice might play a role in facilitating that. The discussion of two concerns of contemporary photographic practice (the material and the social) sheds new light on some of the diverse ways in which contemporary photographic practitioners engage with photographic archives. In doing so, contemporary photographic practice becomes the conduit through which cultural materials conservation practice and emergent archaeological theory can come together and open up a blended space of creative thinking to be applied to reinterpretation of the archive.

ENDNOTES

1. MET’s three working hypotheses are: the hypothesis of the extended mind in which cognition is framed as a process that extends beyond the brain and body out into physical world. The hypothesis of enactive signification in which the material sign is conceived as a part-material, part-mental entity that brings forth meaning through action. The hypothesis of Material Agency proposes ‘agency’ as the ability of objects to effect changes upon the world through human engagement.

2. According to the hypothesis of enactive signification, material semiosis is a cognitive process that functions through a logic that differs from the representational logic that linguistic semiotics rely upon. It proposes that in processes of material semiosis meaning emerges through the conceptual integration of the material and conceptual domains. For further detail on the semiotic basis of MET and the hypothesis of enactive signification see Malafouris (2013, pp. 51, 89-118).

3. According to the hypothesis of the extended mind, material culture and cognition are constitutively intertwined, in that objects act as probes through which humans explore the world. In this manner objects (at least in part) constitute the mind, in that they are part of the brain-body-thing process through which cognition emerges. For further detail on the hypothesis of the extended mind see Malafouris (2013, pp. 57-87).

4. According to the hypothesis of material agency, agency does not lie with objects and humans respectively rather it is exerted and effected during processes of human engagement with objects. For further detail on the hypothesis of material agency see Malafouris (2013, pp. 119-149).

5. Marshall’s professional milieu included sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), art historian Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), classical archaeologist, art historian and curator of antiquities Gisela. M.A. Richter (1882-1972), archaeologist and art historian Bernard Ashmole (1894-1988), classical archaeologist and art historian John Beazley (1885-1970), classicist, curator, museum director Edward Robinson (1858-1931) among others.

6. For further detail on the author’s materially focused creative work with the glass plate negatives of the Marshall Collection see Thormod (2019, pp. 136-143).

7. For further detail on the hypothesis of enactive signification see Iliopolous (2016, p. 256).

8.Crauford (2003 p.107)

9. For further detail on concepts of intentionality and affordance in relation to the hypothesis of material agency see Malafouris (2013, pp. 135-149).

10. The author’s use of the term ‘withness’ intends to describe a materially-stimulated state of being that is experienced as an embodied manifestation of empathic mutuality. The author’s conception of the term withness is based on Michael Polanyi’s (1967, p. 17) conception of the term ‘indwelling’, of which he states, ‘indwelling as derived from the structure of tacit knowing, is far more precisely defined an act than is empathy.’ A photographic antecedent to the author’s conception of the term withness can be found in Walter Benjamin’s (1931, p. 209) use of the term ‘resting’ in his description of what he called ‘the image aura’; describing an image aura as a ‘strange web of time and space’, Benjamin discussed the importance of ‘resting’ with an image ‘until the moment or hour begins to be part of its appearance’. The author’s conception of withness is indebted to Polanyi, Benjamin and Malafouris. For further detail on the related concepts of indwelling and withness see Hazewinkel (2015, pp. 108-150).

11. Figure 7 is directly based on Figure 5.2: Mind Beyond Cognitivism (Malafouris 2004, p. 57). In Malafouris’s original he presents the key terms – embodied, situated, extended, enacted, distributed, mediated – in suggesting how human cognition should be construed. He goes on to provide a list of authors (compiled under each key term) that his own thinking is indebted to (Malafouris 2004, p. 57).

REFERENCES

Benjamin, W 1931, ‘A Short History of Photography’, Screen, vol. 13, issue 1, Spring 1972, pp. 5–26, accessed 6 October 2019, <https://doi-org.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/10.1093/screen/13.1.5>.

Berenson, B 1932, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A list of the principal artists and their works with an index of places, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

British School at Rome (BSR), Faculty of Archaeology, History and Letters, 1927-28, Twenty-Eighth Annual Report to Subscribers, Rome, Italy.

Crauford, A 2003, ‘John Marshall dealer in antiquities and collector of photographs’, History of Photography, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 99-110.

Hazewinkel, A 2015, ‘Stone authority violence, relating body, materials, remembering’, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney.

Iliopoulos, A 2016, ‘The Evolution of Material Signification: Tracing the Origins of Symbolic Body Ornamentation Through a Pragmatic and Enactive Theory of Cognitive Semiotics’, Signs and Society, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 244-277.

Iliopoulos, A 2019, ‘Material Engagement Theory and its Philosophical Ties to Pragmatism’, Phenomenology and Cognitive Sciences, vol. 18, issue 1, pp. 39-63.

Ingold, T 2007, ‘Materials against materiality’, Archaeological Dialogues, Cambridge University Press, vol. 14, no.1, pp. 1-16.

Malafouris, L 2004, ‘The Cognitive Basis of Material Engagement: Where Brain, Body and Culture Conflate’, in E Demarris C Godsen & C Renfrew (eds.), Rethinking Materiality: The Engagement of Mind with the Material World, Macdonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, pp. 53-62.

Malafouris, L 2013, How things shape the mind. A theory of material engagement, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Metropolitan Museum of Art 2018, Greek and Roman Art, History of the Department, accessed 3 November 2018, <https://www.metmuseum.org/press/general-information/2010/greek-and-roman-art>.

Polanyi, M 1967, The Tacit Dimension, Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, New York.

Renfrew, C 2004, ‘Towards a Theory of Material Engagement’, in E Demarris, C Godsen & C Renfrew (eds.), Rethinking Materiality: The Engagement of Mind with the Material World, Macdonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, pp. 22-32.

Thormod, K 2019, ‘Artistic Reconfigurations of Rome: An Alternative Guide to the Eternal City, 1989-2014’, Spatial Practices, vol. 29, Brill Rodopi, Leiden, pp. 136-143.

Žižek, S 2008, Violence. Six sideways reflections, Picador, New York.